I have been reflecting recently on the aims of linguistic anthropology as a practice. It strikes me that the concept can mean very different things to different people, and much of this varied intellectual activity gets washed out in its its confluence with other better-defined disciplines and methods.

So for what it’s worth, this (periodically updated) post is an effort to define what I believe makes linguistic anthropology distinctive and why it is worth pursuing.

What it is

Beliefs about language and how it relates to the world

Linguistic anthropology is all about the social meaning of language and language behaviours. One important area of interest is the commonsense beliefs that people hold about the possibilities of language and how these beliefs are put into practice or expressed as norms. Key to this understanding is a recognition of the diverse strangeness of human beings. Men belonging to certain Indigenous Australian communities have a special lexicon to be used within earshot of their mothers-in-law, while an activist community in Sweden has an agreed-upon vocabulary for reinforcing values of gender equality. A decision to use one language over another in a multilingual north Indian workplace may be motivated by deference, enmity, national politics or a conviction that a given language has an intrinsic power to encapsulate certain ideas while another is deficient. In some parts of the world, people believe they can communicate with their pets while others converse with the dead. Malagasy peasants, for example, use French to address their cattle, or when drunk and boasting. For the most part, these commonsense assumptions could easily be described as ‘language ideologies’, a term defined by Kathryn Woolard as the “socially, politically, and morally loaded cultural assumptions about the way that language works in social life and about the role of particular linguistic forms in a given society”.

Linguistic anthropologists do not care so much about whether any of these beliefs are empirically true, nor whether the practices that stem from them are reasonable. They are much more interested in how such beliefs and practices maintain coherence within their own everyday contexts. In other words, linguistic anthropologists are interested in all the ways in which we systematically connect language to other aspects of our lives: how we organise ourselves as social creatures, how we signal belonging and exclusion, or how we express our values.

Beliefs about the world and how they are enacted through language

Linguistic anthropologists understand that language is not merely representing information in a straightforward denotative way, but is also doing something in the world. That is, they see language-use as a kind of social action. As such they are at home in the stimulating realm of pragmatics, Gricean maxims and speech acts. Within traditional linguistics, these areas of research are often considered peripheral to the ‘real’ work of investigating linguistic structure. My very biased view is that it is this very sociality of language that animates linguistic structure in the first place and serves as its bedrock.

Mary Douglas once wrote that “it is impossible to have social relations without symbolic acts”. Of course, symbolic acts are not necessarily isomorphic with linguistic acts but in practice they are almost always mediated by language in important ways. As Kathryn Graber put it, a “linguistic anthropologist is more likely to take as her starting point the assumption that, through evaluative language and other forms of interaction, we do nothing less than constitute ourselves”. Others have expressed the same kinds of perspectives: that “social life and its materiality are constituted through signifying practices” (Gal 1998); that “social action requires a semiotic basis” (Gal & Irvine 2019); and that language is not “removed from the social structures and processes” but is itself a “form of social action that plays a creative role in the social reproduction of cultural forms” (Kroskrity 2008). I think my favourite account is provided by Tomlinson and Makihara who present this stance as a kind or reverse Whorfianism whereby “language structure does not necessarily shape social reality as an earlier variety of Whorfian linguistic relativism would describe it, but rather that what people do with language has the potential to change social reality, as well as to change language structure” (Tomlinson & Makihara 2009).

This amusing chart by twitterer @koutchoukalimar based on @kjhealy (here) illustrates just how linguistic anthropology can be so profoundly mischaracterised as being based in innatism rather than relativism, but I’m posting it here because it’s still pretty funny.

What it ain’t

For me, linguistic anthropology is first and foremost a form of anthropological knowledge. It analyses language and language-use as a means to understand something about people. This contrasts with what might be called ‘anthropological linguistics’ which gazes in the other direction: it takes human diversity as a starting point for understanding something about language. Of course, any piece of research can be doing both things at more-or-less the same time but it is still worth making the distinction. In my view, all of linguistics as a discipline ought to be pursued as anthropological linguistics otherwise it ends up being boring at best and naïve at worst. I have much more patience for anthropology that is pursued in ignorance of linguistics. Language represents a great deal of what it means to be human but it is not everything.

Sociolinguists in the classical Labovian mould focus on variation in language use, and how differences of linguistic expression correlate, or not, with demographics or distinctions of social identity. The habit of attributing moral or aesthetic value to these real or perceived differences is, I believe, a universal tendency. But linguistic anthropologists are not content with simply cataloguing and measuring these observed differences or attitudes and then moving on. Instead, they want discover how they fit into a wider system of meaning-making, and how this system is historically situated. While sociolinguists might nod vigorously towards ethnography, it is not the aim of the game.

Descriptive and typological linguists, meanwhile, tend to treat languages as more-or-less disembodied objects of study. This is not necessarily a flaw although they are sometimes accused of sidelining and even dehumanising speakers. Their aim, however, is to deliberately extrapolate away social context the better to isolate formal characteristics. In other words, they are posing the question: What can we say about the internal structural properties of a language, or Language, that we can reliably posit in general patterned terms, without recourse to context? Linguistic anthropologists, by contrast, are interested in how these same characteristics are contextually embedded and very often socially connected to phenomena that are not strictly linguistic.

What it means to me

Linguistic anthropology’s overarching analytic frame can be summarised very simply. It’s all about associating linguistic forms with linguistic behaviours and linguistic attitudes, and then situating all three within a bigger social picture. This is another way of describing Silverstein’s concept of the the total linguistic fact. It is not, however, about drawing straightforward causal lines between the three elements. On the contrary, the ways that they are often incommensurate are particularly revealing.

In my view linguistic anthropology suffers from both over-theorisation and under-theorisation. It is over-theorised to the extent that its practitioners can be very good at coming up with increasingly refined analytic models to apply to increasingly refined (and perhaps increasingly trivial) linguistic or social phenomena. It’s under-theorised because surprisingly few can provide a confident reason for why language should provide such a critical entry point for addressing foundational anthropological questions such as “What does the world mean to people? How are we all similar and how are we all different? Why do we entertain ideas and behave in ways that appear to contradict common sense?”

And what I’m doing with it

Language is less like a programming code distributing informational bits, and more like a multi-purpose tool that is crafted and re-crafted in the process of its use in real interactions. As a system of representation it is rigid enough to perform high-precision work under pressure, and versatile enough to adapt and change quickly. To my mind it is this peculiar property that makes language such a powerful and interesting phenomenon since it lends itself to strategic manipulations. (Enfield’s take on this is perhaps better informed. He argues that language lends itself to strategic manipulations specifically because it is not a high-precision tool.)

Languages can be imagined as evolving biological organisms, to the extent that we receive them as ready made and fully structured. This structure, and our awareness of it, presents an easy analogy for the systematicity we perceive around us in our relationships with one another and the world at large.

It is not the goal of linguistic anthropologists to reify this awareness. We do not, with Lacan, wish to claim that the “unconscious is structured like a language” nor that Eskimos have an especially nuanced appreciation of snow. Rather, we delight in the very existence of these analogies and what they entail about us as a reflective species.

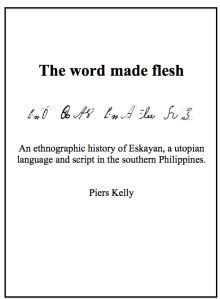

For all these reasons I am interested in situations in which people actively manipulate the systematic properties of language to pursue wider social objectives. At the moment I’m exploring writing systems as a very human and very artificial extension of our communicative potential. I think, at heart, it is the artificialness of writing systems that intrigues me. After all, there is no such thing as a natural script. All writing originates in conscious creative effort, even if it can evolve in ways that are not consciously directed. In this light I’m interested in how James Paul Gee defines literacy. For Gee, literacy is not the capacity to interpret graphic symbols as linguistic values, but rather the “control of secondary uses of language (i.e. uses of language in secondary discourses)” (Gee 1989). While I am definitely a narrowist when it comes to definitions of writing, I am a broadist when it comes to literacy as a discursive practice.

Writing may extend the potential of language but it also operates as a constraint on it, and like all good constraints it encourages formal innovation. Those who decide to write a piece of text usually do so in the knowledge that their audience is not in the same time or place as they are. This promotes a certain self-consciousness of expression, and the very pragmatic need to contextualise and to establish conventions. But counterintuitively, writing is so often naturalised or invisibilised. Far from being a game-changer that reorganises cognition and revolutionises the dynamics of knowledge (per Jack Goody), writing is regularly deployed in defence of existing social relations and conventions (per Maurice Bloch). In this way, culture-specific literacy ideologies can end up having a similar logic to the culture-specific language ideologies, outlined above.

Writing is, however, just one kind of graphic communication device. Across the world there are graphic codes that do not encode any linguistic structure and rely on a supplementary oral channel to be activated. Such systems, including Australian message sticks, Andean khipus and north American mnemonic codes, traverse the ambiguous gap between orality and the written word. The artefacts left behind in museums may be silent, but patient historical ethnography is allowing us to reconstruct the principles of communication and restore their meanings.