I’ve recently read four pieces of writing that together tell an interesting story: David Uniapon’s Legendary tales of the Australian Aborigines [1924-1925] (2001), W. E. H. Stanner’s “The Dreaming”(1953), Patrick Wolfe’s “On being woken up: the Dreamtime in anthropology and in Australian settler culture” (1991), and Howard Morphy’s “Empiricism to metaphysics: In defence of the concept of the Dreamtime” (1997).

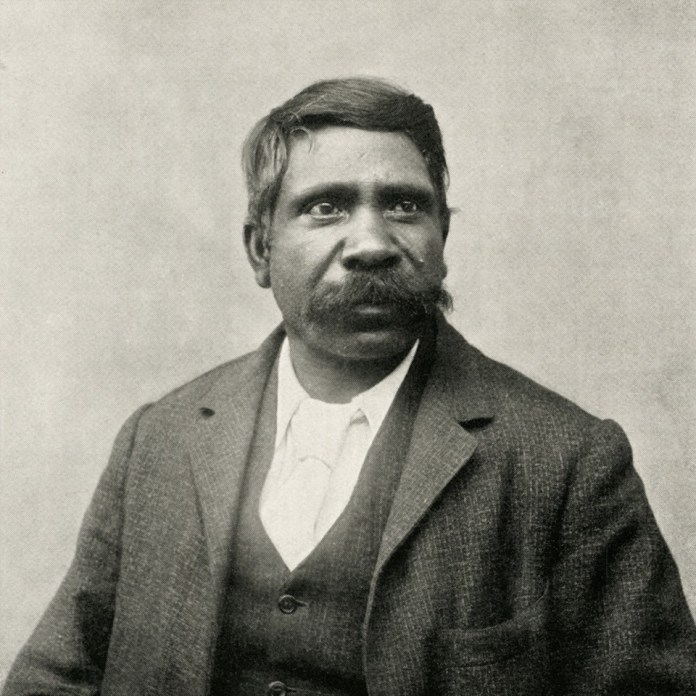

On the face of it, the odd one out is Unaipon’s Legendary tales. In the preface to his original manuscripts, he wrote: “Perhaps some day Australian writers will use Aboriginal myths and weave literature from them, the same as other writers have done with the Roman, Greek, Norse, and Arthurian legends”. Arguably this was his true project. Unaipon saw himself as doing the foundational work of transforming an ancient oral tradition into a literary one, like Homer before him, or the Brothers Grimm. In fact just like the Grimms he travelled widely in the aftermath of deadly wars, meeting storytellers well beyond his own Country to preserve their narrative traditions in more consumable folkloristic prose. At the same time this was a shrewd accommodation to the literary market in which he was operating, making the subsequent theft of his work by W. Ramsay-Smith all the more poignant.

The result is a representation of the Dreaming that evokes C. S. Lewis and Beatrix Potter, much more than say the Songs of Central Australia as transcribed in Arrernte by T. G. H. Strehlow. For Unaipon, the momentum and delight of the story appears to take precedence over the ‘authenticity’ of the original performance or even the religious or moral significance of the narrative itself. In accommodating to Edwardian sensibilities Unaipon also avoids relating creative tales involving bodily emissions, or sex specifically, that punctuate more traditional tellings. And yet after reading a number of the legends in succession, you begin to get a more subtle sense of the Dreaming that underlies it. I noticed, for example, that the heroic participants are all embodiments of totemic animals, captive to their own peculiar behaviours and obligations. They swim, hop, and fly. They are wise or aggressive, honest or deceitful. Their ritual commitments to Country and to kin are never seen as distinct from ordinary instinct or ecological survival. At the same time they represented as fully human actors. The Crow is is a man with human limbs and organs but he will also fly or carry things in his beak. This singularity is captured by T. G. H. Strehlow who observes that in Aranda songs an individual is completely identified with their totem, such that “[t]he willy wagtail woman […] is clearly imagined to be a bird pecking at a real snake” (Songs of Central Australia, 181). At a wider scale, Unaipon subtly reveals deeper relationships between totems. They resolve into moiety divisions that in turn govern marriage and family relations, the violation of which provokes crisis and tragedy, much like Oedipus, Snow White or Hamlet.

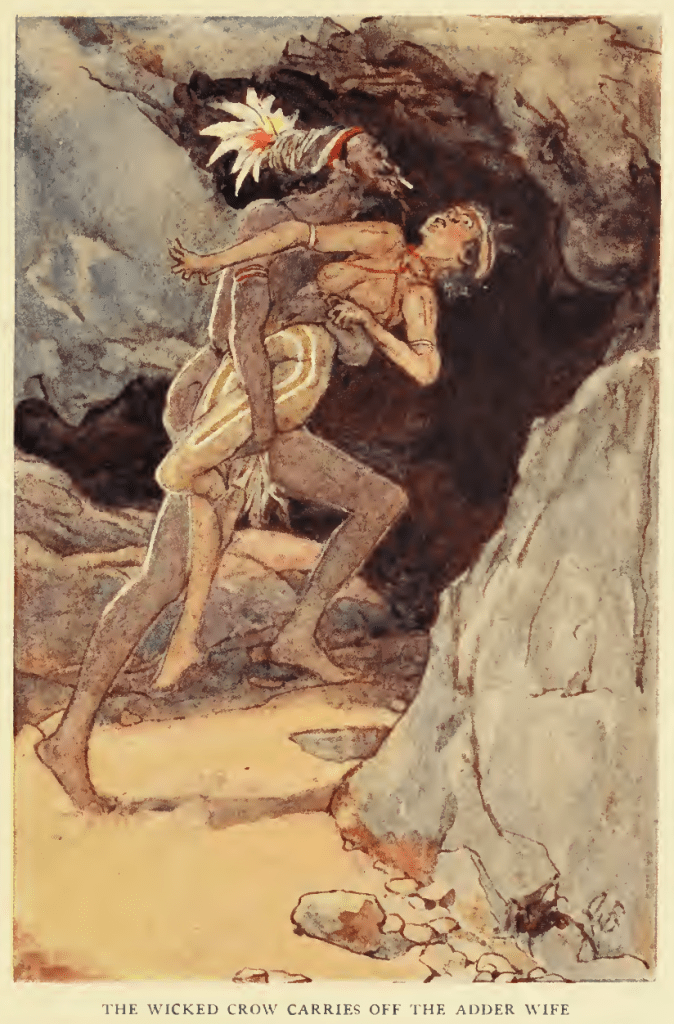

Illustration from the 1932 ‘Ramsay-Smith’ edition.

W. E. H. Stanner’s impressive attempt to translate the theoretical concept of the Dreaming is a helpful gloss on Unaipon’s own linguistic and cultural translations. If you set aside Stanner’s structuralist fallacy that Australian Aboriginal societies are somehow ahistorical in their so-called ‘abidingness’, his analysis has otherwise stood the test of time. He certainly understood his assumed reader in his deliberate use of Western-inspired metaphors to clarify an otherwise head-spinning concept. Namely, the ‘everywhen’ (Tjukurrpa, Alcheringa, Wangarr, etc). Stanner recognised that the Dreaming has an apparently paradoxical chronotope. The narratives are not set in a past time, but are perpetually occurring in all time and within specific landscapes and living individuals who embody ancestral beings. The Dreaming, as he understands it is “a kind of narrative of things that once happened; a kind of charter of things that still happen; and a kind of logos or principle of order transcending everything significant for Aboriginal man”. If Unaipon’s translation of the Dreaming is linguistic and literary, Stanner’s translation is metaphysical, but not strictly mystical.

This brings me to Patrick Wolfe’s critique as the real odd one out. For Wolfe, the Dreaming is merely a propagandistic construct of the colony designed to subordinate and ‘other’ Aboriginal people. Or as he baldly put it “the Dreaming complex constituted an ideological elaboration of the doctrine of terra nullius […]”. Worse, the metaphor of dreaming encourages an extension of the analogy, whereby colonial invasion is a form of waking up to reality. In this formulation, somebody like Unaipon could only serve as the dupe of Empire, dutifully reproducing infantilising stereotypes to the detriment of his own people. Stanner meanwhile is cast as a romantic, captured by the colonial fantasy of the childlike primitive who is incapable of modernity and in need of protection.

Wolfe’s essay is very much a product of the early 1990s, a time of exciting iconoclasm in the humanities where various forms of reflexive critique were seen as daring and important. Empirical reasoning was merely the stale legacy of European positivism, and what mattered was discursive thinness over ethnographic thickness, floating signifiers over the more challenging signifieds, the slick cleverness of Cultural Studies over a retrograde and outmoded Anthropology.

But when you peel back the veneer of Wolfe’s argumentation, his commentary is vacuous and uninformed, a fact that Morphy recognised at the time it was written. It seems odd to have to say it but no, the Dreaming is absolutely not an invention of the colonial state but a well-established and widespread complex of concepts found across unrelated language-groups and with continuing relevance today, even if it does not point to any universal Aboriginal cosmology.

With characteristic patience and attention to detail Morphy is able to separate the Dreaming as a tradition, from the historical English etymology of ‘the Dreaming’, from the Dreaming as popular construct in settler and Aboriginal communities today. Morphy’s critique of Wolfe is well worth reading, not as a triumphant take-down of bad scholarship but as a clear intellectual account of a tricky concept that rewards the hard work of analysis. Morphy argues, persuasively, that anthropology is not only a poor scapegoat for colonial crimes, but that its methodology offers that greatest hope for crosscultural understanding. In a word, anthropology can be a formidable battering ram to ethnocentrism, even and especially to the legacy of ethnocentrism that was historically encouraged within the discipline itself.

By contrast, what interests me about Wolfe’s wildly daft essay is how its ‘reasoning’ is wholly consistent with the new reactionary politics now ascendant in the Anglosphere. Many have already noticed that the postmodern scepticism of the 1980s and 1990s has been reincarnated, in grotesque fashion, by radical ultracons who speak unselfconsciously about alternative facts and fake news and the repudiation of science. Today, Wolfe’s ‘analysis’ looks so much closer to the sophistry of Jordan Peterson and his supporters than subversive scholarship. This is the well-worn debate-me-bro shuffle that involves burrowing into detail to avoid addressing the bigger conceptual picture, but them zooming straight in the bigger picture to distance oneself from inconvenient facts on the ground.

It’s also making me think about present incarnations of reactionary postmodernism in Aboriginal discourse, especially when it’s represented in a progressive guise. In progressive politics, there is conscious move to draw attention to the less-examined possibilities of Aboriginal culture, but this is sometimes done by resorting to the imagination rather than hard work of doing the reading. As a result we are now confronted with exciting but uninformed claims about subsistence, warfare, sacredness, gender, learning styles etc. These are seen by their proponents as bravely overturning the narrative—a worthy counterpunch to the big nationalist projects promoted on the right—when in fact they are usually reinforcing colonial values and stereotypes through the back door. Aboriginal techniques and practices are revealed to have value only to the extent that they are deemed to be ‘sophisticated’, which typically means that they have some kind of recognisable Western counterpart. What’s also worrying is the unspoken prejudice that Indigenous knowledge systems are somehow unrigorous—or even unknowable—and therefore up for grabs, a screen for projecting radical possibilities.

Stanner cautioned against such breezy and mystical approaches to Aboriginal knowledge systems with an apt analogy: “And if one wishes to see a really brilliant demonstration of deductive thought, one has only to see a blackfellow tracking a wounded kangaroo, and persuade him to say why he interprets given signs in a certain way.” In other words, hypothesis-driven thinking does not belong to the West. Sadly, the trope of the intuitively-unconstrained-blackfella remains alive and well, the torch carried forward from Daisy Bates, to Marlo Morgan, to Tyson Yunkaporta.

Productive comparisons to the West, meanwhile, are not without their own value. Unaipon did it when he compared Aboriginal literature to the oral epics of Europe. Later this comparison would be independently reprised by Clunies-Ross (1983, 1986) and Cataldi (2001). Stanner largely compared through opposition by explaining how the Dreaming is not like the Old Testament, nor is it like Scandinavian, Indian, or Polynesian mythologies. The problem is when the illuminating metaphor—or counter-metaphor—becomes the unacknowledged standard, that is naturalised and rendered invisible. Skilful cultural translation should instead be about trying to understand a system or practice on its own terms and using creative metaphors to make the familiar strange and the strange familiar.

For somebody like me who was raised in a Western European narrative tradition, reading Unaipon’s Edwardian translation of the Dreaming allows me to gaze back and to intuit a more totemic, Dreaming-like dimension to the tales that I was raised with, from the Wind in the Willows—Frog and Toad are simultaneously amphibians and real people in contrasting marriageable moieties—to Rumplestiltskin who violates the moral imperative of reciprocity by falsely invoking a naming taboo. Michaels (1986, cited in Walsh 2016) has an great example of film criticism through a lens of Warlpiri kinship: “[…]there are intriguing questions that Aboriginal viewers brought to a movie like Rocky: Where were Rocky’s father’s brothers? Who was taking care of his old mother?”.

All the while we can also accept the risk that translation, in either direction, will be distorted. In the best cases, this distortion amounts to radio static rather than corruption. It is not a pretext for rejecting the possibility of translation, nor should it be used, per Wolfe, to generate satisfying conspiracies about The Colony and what it truly desires. Worse, Wolfe’s fantasy of the Dreaming-as-double-consciouness leaves nothing to fill the conceptual vacuum. If Aboriginal people have really been imprisoned by a foreign ontology, what were the existing ‘authentic’ beliefs and behaviours from which they have strayed? This is not a viable challenge for (reactionary) postmodernists for whom either nothing is ‘authentic’ or everything is ‘authentic’ since we are only ever dealing with surfaces and sensations. It’s also a familiar manoeuvre of 1990s critical theory, which was often about critique for it’s own sake, a game in which the winner is the one with no cards left in their hand.1 To paraphrase Contrapoints: they didn’t want knowledge, they wanted to endlessly “critique” knowledge.

I’m a newcomer to the Dreaming and I’m not sure how my thoughts will evolve, but I feel confident that the Dreaming is indifferent to the West’s epistemological nightmare of its own making. I enjoy reading Unaipon’s translations in the same way that I will always get a kick out of exploring modern interpretations of Shakespeare, Austen or Conan Doyle. These stories have sufficient universal appeal that they can accommodate diverse retellings.

After all, despite the fact that elements of Dreaming stories are prone to change with each new generation of storytellers, the Dreaming itself has survived as a narrative practice of value-making in Indigenous communities, and no doubt will continue to survive as a model for organising belief and action, law and meaning.

Clunies Ross, M. 1983. Two Aboriginal oral texts from Arnhem Land, North Australia, and

their cultural context. In S. Knight & S.N. Mukherjee (Eds.), Words and worlds: Studies in

the social role of verbal culture (pp. 3–30). Sydney: Association for Studies in Society and

Culture.

Clunies Ross, M. 1986. Australian Aboriginal oral traditions. Oral Tradition, 1(2), 231–271.

Stanner, William EH. 1979. White man got no dreaming: Essays 1938-1973. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Unaipon, David. [1924-1925] 2001. Legendary tales of the Australian Aborigines. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Walsh, Michael. 2016. “Ten postulates concerning narrative in Aboriginal Australia.” Narrative Inquiry 26 (2):193-216.

This blog is rarely updated! If you want an email notification whenever there is a new post, click on the follow button right at the top ↑ that looks like this:

- I wish I could remember where this analogy came from! ↩︎