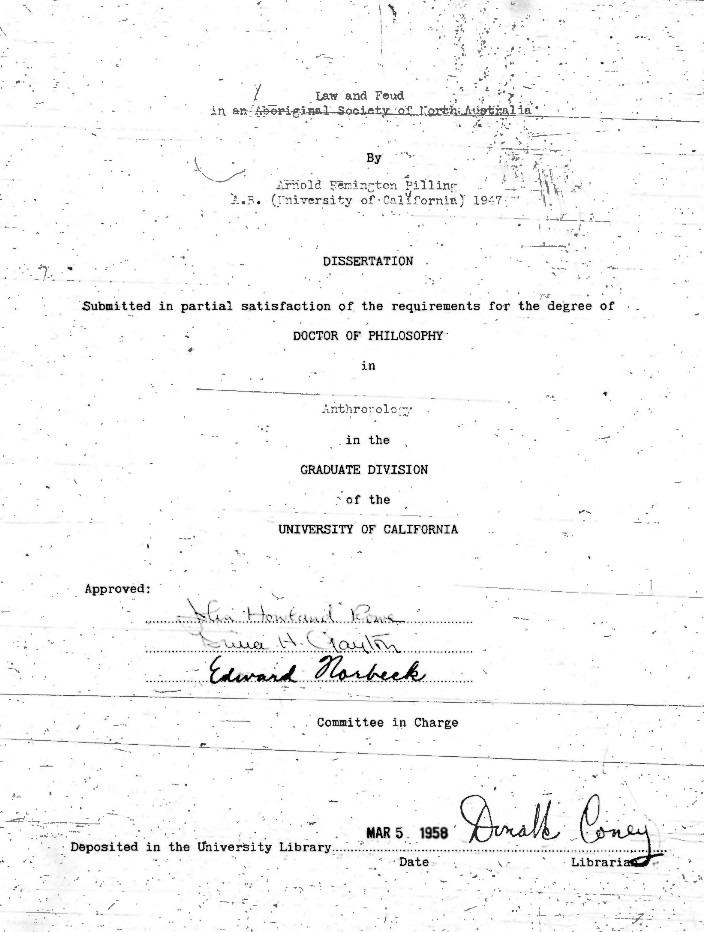

A few years ago, William Buckner at the Human Systems and Behavior Lab told me about the 1958 PhD thesis Law and feud in an Aboriginal society of north Australia by Arnold Remington Pilling. Buckner provided me with jpg images of each page but through a happy error in the inter-library loan system I managed to get hold of the actual microfiche and digitise it. You can now get hold of it here.

I found this thesis to be absolutely captivating. Pilling was a Fulbright scholar who stayed at the Bathurst Island Mission for eighteen months between 1953 and 1954. His fieldwork was about the legal practices of Tiwi islanders within a broad framework of comparative law, but the result turns out to be a brilliant record of detailed oral history. His main consultant was a man known only as Cabbagie, who I have since identified as Purrumayilimirri, the grandfather of my principal consultant in the Tiwi Islands.

One thing I enjoy about Pilling’s writing is that it stands apart from the classic tradition of researchers claiming to be more competent than they really are. Everyone’s familiar with a particular variation of the “mystique of fieldwork” trope in which the rugged scholar triumphs heroically over all difficulties and of integrates themselves seamlessly into the societies they study. PhD candidates in particular have a perverse incentive to hide or disguise their vulnerabilities, knowing that they will eventually have to face examination. But even seasoned scholars have an unfortunate tendency to swagger. Here is Margaret Mead boasting about her linguistic competence on Manus:

From a thatched house on pile, built in the center of the Manus village of Peri, I learned the native language, the children’s games, the intricacies of social organization, economic custom, and religious belief… I learned to know intimately enough not to offend against the hundreds of name taboos.

To which her collaborator Lola Romanucci-Ross would later write:

I am quite sure Mead did not ever learn three languages in one year or even one language in three years. She had several formidable talents, but the ability (or desire?) to master a foreign language was not among them.

Pilling, meanwhile, is blisteringly honest about his linguistic and cultural shortcomings, even when his candour doesn’t reflect well on him. He devotes a great deal of space to setting out his process, how it went wrong as well as right, and when and why he decided to compromise his methods in a given instance. Unusually for the 1950s he recognises the ethnographic talents of his consultants, observing how they trained each other and adjusted to his demands.

I rarely needed to interrupt him or ask for further data concerning the openings or conclusions of cases. Cabbagie even proved capable of eliciting satisfactory accounts from others. For instance, when one of his elderly clan “sisters” [PK: classificatory female sibling] reported in a confused manner upon a recent scandal, he stopped her and told her to begin at the beginning “just the way policeman want” (LVIII, p. 161). Ultimately, others in Cabbagie’s camp realized my interest in detail and told versions which were rich in particulars. (Pilling 1958, 8)

Aboriginal communities have a long inter-generational history of white researchers entering their spaces to ask questions, and it’s not uncommon to find individuals who are well trained in, for example, linguistic elicitation or ethnographic description and who have passed those skills onwards. Even in relatively early contact scenarios talented Aboriginal linguists and anthropologists come out of the woodwork to produce insightful work for the benefit of bewildered white researchers. One example is Toolabar (Tulapa), who assited A. W. Howitt in the 1870s. He developed a method of representing kinship relations with sticks to reveal the persistent classificatory connections and circumvent the need for lengthy family trees. It’s a method I’m rebooting in order to represent triadic message stick encounters. Another is the linguist Patyegarang who expertly described the Eora language in collaboration with William Dawes. More recently, the Arrerrnte artist Jim Kite Erlikilyika joined Spencer and Gillen on their 1901-1902 expedition, interviewing consultants and producing illustrations. For Pilling to find Cabbagie was a lucky break. Cabbagie was not Pilling’s only collaborator of course, but his clear capabilities as a competent oral historian, ethnographer and teacher shine through the work.

Oral history

Applying the so-called “case method” the aim of the thesis was to record both historical and contemporary legal disputes that were resolved according to traditional law. Pilling then sets out 107 individual cases of breaches of traditional law— including cases of theft, aggression, kidnapping and murder—and lays them out in forensic detail as if they were going to be compiled in a heavy-bound law journal. One of the cases goes all the way back to 1818. (He mentions, in passing, another 127 Mission-period cases that remained in his notebooks.)

I can’t judge it as a work of comparative law, but it is a outstanding example of a piece of research that aims to do one thing—describe the fundamentals of Tiwi traditional law—and ends up doing something perhaps even more valuable—provide a rigorous historical account of salient events in the lives of Tiwi islanders over many generations. This, too, in a part of the world where formal archives are frustratingly sparse.

His oral historical methodology is also impressive for the time, especially the way he respects contrary representations from different authorities, describes in-group Tiwi criteria for authenticating an account, and even explains when deliberate fabrications are considered politically necessary by his consultants. The stories are rich in detail and since the participants are named there is every reason to suppose that their descendants will recognise them and benefit from this work. Disappointingly, there are no cases or stories about interactions with Makassan trepangers because the custodian of those stories had recently passed away when Pilling was there, meaning that these specific narratives were under a period of taboo.

Message sticks

My primary interest was in the ways message sticks were used in calling the community to traditional fights or other legal events. It is clear from his documentation that message sticks were not part of the traditional repertoire of Tiwi Islanders but were introduced by Iwaidja buffalo shooters from the mainland in about 1916, in other words after the mission was established in 1911. Apart from this thesis, I can think of no other piece of documentation that sheds any real light on the historical diffusion of this technology anywhere else in Australia, though it must have been spreading during the period of colonial expansion across many parts of the mainland.

He observes that messengers were either men of clans represented in the enemy camp or women who had close relatives in the enemy camp. The use of women as messengers in this way speaks to the diffusion of the system from the Iwaidja: this is one of only a few groups in Australia where women were known to be appointed as messengers. And as far as I know, it is only among the Diari of South Australia where messengers had to be women although they did not use message sticks for this task.

Message sticks were being sent and received while Pilling was doing his fieldwork. C. P. Mountford would visit the islands in 1954, but the two men never met. At this time Mountford put a lot of effort into describing and sketching Tiwi message sticks and his book The Tiwi: Their art, myth, and ceremony (1958) represents the last ever published research on message sticks based on fieldwork. Mountford seemed to suggest that message sticks had recently gone out of use, but it’s not clear if he was talking about message sticks generally or simply message sticks with totemic designs. He wrote:

Although the general distribution of the totemic purunkitas [message sticks] has been discontinued in recent years, the aborigines who knew them well, made nine examples for me.

In any case it was probably at about this time that the use of traditional message sticks went into decline barely a few decades after it had been introduced. Certainly when I interviewed Cabbagie’s grandson on Bathurst Island in 2019, he lamented that the old people had not passed on any traditional knowledge to him about message sticks, even though he still had several stories about them that he could recall in detail. Yet it was also in the 1950s when modern message stick communication emerged in the Tiwi Islands and elsewhere in the north. By ‘modern’ I mean the contemporary practise of issuing message sticks to significant leaders as a way of formalising a diplomatic relationship between an Aboriginal community and a white institution. In 1951 a Melville Island man, identified only as Un-Tu-Looie sent a message stick to Prime Minister Menzies and another to the Northern Territory administrator A. R. Driver. Message sticks have since been sent to subsequent prime ministers and to British royalty.

Song

Another fascinating system of conveying messages between opposing groups on the Tiwi Islands was through song. Songs that were originally composed for a specific ceremony were repurposed for transmitting news or just displaying talent. But some songs were sung in public, in order to make a face-saving point. In these cases it was the connotations of the song rather than precise content of it, that constituted the intended message. Pilling writes:

Many of the songs sung by males at Bathurst Island were initially composed for a Kulama, the annual first fruit rite of Bathurst and Melville Islanders, and were later resung by their composers and others as popular ballads. The words and interpretation of such a song passed through the camp as a means of repeating exciting news and a display of the most recent production of a popular art form. The message borne by a song was carried by visitors to other camps, and, finally, the song reached the audience for whom it was intended. In many cases, a song and its interpretation were a reference by its composer to some wrong done him and statement of the type of sanction which he would impose to punish his injurer. (98)

For me this is a really clear illustration of the importance of intermediaries in Aboriginal communities generally. When it comes to discussing something of an even a vaguely sensitive nature, it pays to take an indirect approach. (A German linguist colleague told me his theory that Anglo-Australians have an advantage working in Indigenous communities because we have inherited a kind of British indirectness and subtlety, while he barges in with Teutonic directness and scares everyone off). This is more obvious when it comes to mother-in-law avoidance, the use of sign languages in particular contexts, and of course with message sticks that rely on an intermediary, as well as the externalised embodiment of the message in an object.

In the Tiwi islands, the kinds of confronting issues conveyed through the connotations of an overheard song included the desired payment of a debt, for example, in terms of marriage exchange or for the composition of a mourning song. Other songs would be interpreted to mean that the singer was aware that someone was telling false stories about him, or they might be a warning for an impending revenge killing. What’s interesting is that when the issue was brought forward through song, it allowed the person in the ‘wrong’ to come forward and resolve the issue without violence. The stakes are incredibly high yet there is great nuance and delicacy in this kind of communication given that the songs themselves are ostensibly about other unrelated topics. The singer can always deny they were trying to influence the interlocutor, and the interlocutor can appear to be making sincere amends as if they had recognised the injustice themselves and not been prompted. I’m reminded of similar styles of interaction among the Ngaanyatjarra, described by Inge Kral, and Elizabeth Marrkilyi Giles Ellis. In the pre-dawn darkness, Ngaanyatjarra people regularly used a speech style known as yaarlpirri, through which news and plans could be called out to the camp. It was also a time of morning when individuals could semi-anonymously air their grievances on the understanding that no reprisals could be made in that instance for raising a sensitive matter in public.

With thanks to Hannah Bulloch for the Mead and Romanucci-Ross quotations.

[Update: On the topic of skilled Aboriginal ethnographers, a colleague has pointed me to Peter Sutton’s The politics of suffering, chapter 7 ‘Unusual couples’]

Piers – thanks so much for making this available. Pilling is well-known to us here at Wayne State – he arrived in 1958 shortly after finishing his dissertation and spent the rest of his career here until his death in 1994, and was a co-founder of our Museum of Anthropology. Most of his later work was in historical archaeology, but he was also a founding member and executive of the Society for Lesbian and Gay Anthropologists (now the Association for Queer Anthropology). We have literally thousands of pages of his material and countless artifacts here at the museum as well as our archives. In my history of anthro class this semester I have an honors student doing a project on Pilling’s early years at Wayne, and I’ll be sure to direct her to this thesis. Thanks! – Steve

Hi Steve, this is fantastic. I ended up finding Pilling’s obituary notice (https://sha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/29-4-Memorial-Pilling.pdf) and it was a relief to learn that he established such a fine career. I’d forgotten that you were at WSU and I wrote directly to the Museum of Anthropology asking about his abundant notebooks from the Tiwi islands, all conveniently numbered in his thesis. Needless to say, this would be an extraordinary resource to share with Tiwi islanders today and with historians working in this part of the world. Is there any scope for these fieldnotes to be digitised?

The short answer is yes, maybe. There is definitely a desire to get the old stuff sorted and archived properly, which would presumably include any Tiwi stuff that’s around. The museum is better-funded than it has been in the past but there are a lot of priorities and the Michigan material is more in line with the museum’s mission and so probably it has not been a high priority. But shoot me an email to keep it on my radar and I’ll nudge the appropriate people in the right direction.

Great thanks! As far as my own research is concerned I’m content with Pilling’s dissertation and published materials, but I know that the fieldnotes would have great value in Australia in many different quarters, from Stolen Generation research to heritage management. I’ll send you an email shortly.