It’s been some time now since the World Scripts Winter Academy at the University of Cape Town came to an end.

Organised this year in the framework of Zukunfstphilologie, an initiative of the Forum Transregionale Studien (Berlin), academies are held by the Forum and the Max Weber Foundation- German Institutes Abroad twice a year on different themes at various locations. This year it took place in Cape Town on the theme of “World Scripts: Concepts and Practices of Writing from a Comparative Perspective“.

(Details, photos and recordings are on the official World Scripts blog.)

Image by Forum Transregionale Studien. From left to right: Abdur Rahoof Ottathingal, Meikal Mumin, Nir Shafir, Naveen Kanalu, Olly Akkerman, Australian Git, Shamil Jeppie, Judith Bihr, Susana Mollins Lliteras, Lena Salaymeh, Arun Rasiah.

Islam Dayeh, co-director of Zukunfstphilologie, declared World Scripts to be “the best Winter Academy ever”. For my part, the event passed all my expectations. It was possibly the most rewarding conference experience I’ve ever had. I learnt a great deal about African and Middle Eastern scripts and traditions, but here are just few of the more general insights I took from the Academy:

1) Nobody is a philologist

The world’s last philologist, pictured in Tasmania in 1933

Sadly, the last philologist died in captivity in 1936 without offspring. On the up side, this has allowed the term ‘philology’ to be rescued from its fustian association with bearded Europeans in armchairs and repositioned as a more exciting post-colonial, post-structural, not-exclusively-Western enterprise. My best attempt at defining philology would be something like “The linguistically informed analysis of texts, their associated technologies and their traditions of reading and reproduction”. A bit like linguistic-anthropology-meets-literary-theory-and-manuscript-history.

2) Humility is a defining characteristic of true intellectualism

Research is not rock and roll. Yes, it’s true that having a PhD or any higher degree has value in the labour market but this does not mean that academic work is more important than other kinds of work, nor that it has intrinsic glamour from the perspective of outsiders. If academia has any ‘prestige’ it is the kind that is counterfeited and dishonestly circulated by academics themselves.

“Philology is just about the least with-it, least sexy and most unmodern of any of the branches of learning associated with humanism” —Edward Said

Perhaps because philology is so uncool to begin with, there was no swagger among the thirty-odd scholars from around the world who participated, and this made a real difference. In such an egalitarian environment nobody was afraid of admitting doubt or exploring ambiguity. As a result, discussions moved quickly towards the most crucial issues without getting mired in pedantry.

3) Diversity is as important as cross-disciplinarity

Almost as many countries were represented as participants, with a good balance of genders, ages and levels of experience. This mattered for the quality of the discussion. English was the native language of only a handful of us. (The remaining participants were forced to yield to our Anglophone imperialism!)

4) Philology has the potential to be a critical ‘Anthropology of the Good’

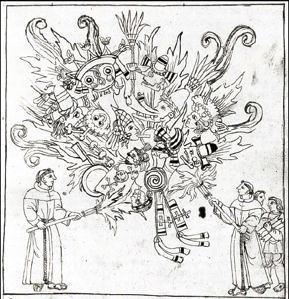

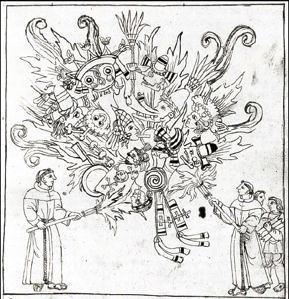

Franciscan monks burning books, 1585

The relationship between people and writing is fraught. On the one hand, writing can be understood as a process of alienation in which meanings are separated from those who produce them and from the context of utterance. But for the same reasons writing and reading can also be experienced as transcendence. Scripts have a capacity to embody or index the beyond, with all the joy and terror that experience entails. Liem Vu Duc—whose own research explores the terrifying (to me) terrain of the Vietnamese bureaucratic manuscript tradition—raised the provocative question of whether writing is necessary for the good life. On the same theme Federico Navarrete Linares described the way that Mexican codices were seen to condense signifier and signified such that the world of gods and monsters was utterly embodied in the text. But he also drew attention to Amazonian traditions of consciously rejecting writing as a practice. All this puts me in mind of Joel Robbins’ paper ‘Beyond the suffering subject: Toward an anthropology of the good’ (2013). Robbins’ powerful idea is to take emic ideas of happiness and fulfillment seriously. The mission of philology—which after all is etymologically a love of letters or the logos—might be about considering the ways in which texts enable or prevent the expression of human happiness.

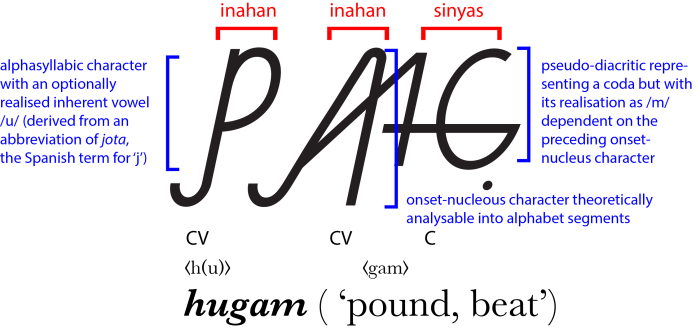

5) Beware of notions of deficiency – they can always be historicised

Writing is a curiously imperfect technology, and scripts are like tools that can do one very specific job. What happens when the tool is borrowed for a completely different job? Or when the ‘job’ itself changes? In these scenarios it’s tempting to see the tool itself as deficient. This may well be the case, but deficiency is relative to an historical moment. Sometimes, ideologies of modernity will occlude the historical particularities of ‘deficient’ scripts in order to draw an analogy between script reform and a collective moral reform. Various presentations touched on this issue as it has played out historically, but I was particularly interested in Lena Salaymeh’s discussion of the role that ideology plays when it comes to contemporary decisions about how to Romanise words in Arabic script – and that these decisions can affect actual semantics and reception.

6) Modernity is a powerfully paradoxical idea

Caricature of the ‘Chinese typewriter’, shown by Tom Mullaney

Related to the themes of script reform is the slippery idea of modernity itself. To some extent modernity is sustained by a claim to universality and normativity, but in practice it is imagined, future-projected, and historically and geographically relative. In this sense, modernity is a desirable but never-quite-achieved state, having much in common with ideologies of nationhood or even subjectivity. It’s easy to see how scripts can come to represent ideas of modernity—as discussed in Erdem Aydin’s presentations on the Ottoman script—or its opposite, as in Tom Mullaney’s account of the Chinese typewriter (and congratulations, Tom, for incorporating both MC Hammer and the décor of the seminar room into your analysis).

7) Scripts are imbued with a surplus of meaning

Scripts are contentless and, in most cases, authorless. As Tom Mullaney pointed out, if scripts were inherently meaningful they would not require deciphering. The invention of the telegram, the typewriter and unicode created new problems to address and new opportunities for imposing national, imperial, nativist or utopian ideologies onto writing systems.

8) After the author died, the reader went missing

Conservative literary critics might still be transiting through the denial or bargaining stages following the death of the author. But what of the status of the reader? Michael Allan reminded us that a preconception of the ‘ideal reader’ is always implied in the text, even though such a reader does not exist in practice, and several presentations relativised reading in a striking way.

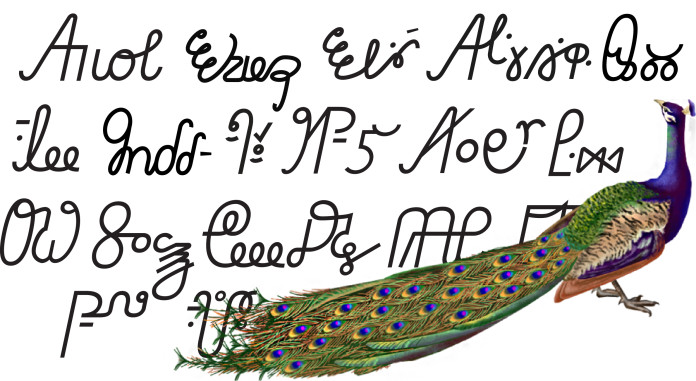

Bodhisattva Kar’s “Reading Stones, Writing Skins: The Savage Naga and the Limits of Language” considered J.H. Hutton’s colonial ethnography of the Naga of Burma. Hutton was fascinated by Naga practices of tattooing and the manufacture of stone artefacts. In Hutton’s estimation these were texts that he assumed to be intelligible but only on his own terms. As Bodhi put it, Hutton assumed that “the native writes his own culture without being able to read it himself”. Hanna Nieber’s creative multimedia account of the practice of drinking the Qur’an in Zanzibar described the body as a reading subject. Qu’ranic verses are written on a white plate using saffron ink then washed off into vessel. The body of the patient is healed when the liquid is consumed and ‘read’ by it. In fact ritual efficacy may be diminished if the patient were to inadvertently read the text with their eyes, before it is washed off. Margherita Trento’s presentation explored how Catholic missionaries attempted to nativise Christian discourse through the circulation of specially formulated catechisms, doctrinal treatises and prayer books in early modern south India. Choice of script and orthography was crucial to the spiritual authority of the text, particularly in the face of rival Lutheran printing presses. It struck me, in this battle for control of the discourse, how the presumptive reader became sidelined such that texts are characterised as being in dialogue or opposition with other texts without a reading intermediary.

9) … but manuscripts do not burn

The update from Susana Molins Lliteras on the Tombouctou Manuscripts Project contained a good news story, at least for an ignoramus like me. Remember when rebels sacked Timbuktu in 2013 and burned a whole lot of manuscripts? Not so much. In Susana’s analysis, the famous image of the pile of ashes is likely to have been a result of burning boxes that the manuscripts were contained in. Other missing documents were probably sold by the rebels, not destroyed. In fact, one positive outcome of the attack is that it drew the world’s attention to the fragility of the materials, making preservation work administratively easier.

The update from Susana Molins Lliteras on the Tombouctou Manuscripts Project contained a good news story, at least for an ignoramus like me. Remember when rebels sacked Timbuktu in 2013 and burned a whole lot of manuscripts? Not so much. In Susana’s analysis, the famous image of the pile of ashes is likely to have been a result of burning boxes that the manuscripts were contained in. Other missing documents were probably sold by the rebels, not destroyed. In fact, one positive outcome of the attack is that it drew the world’s attention to the fragility of the materials, making preservation work administratively easier.

“Manuscripts do not burn”

—Mikhail Bulgakov

I could only catch the end of Federico Navarrete’s talk, but the great conflagration of Mexican codices on the part of missionaries in the period of early contact was also not as devastating to cultural heritage as might be imagined. Federico noted that hundreds of codices continued to be produced after Spanish conquest in Meso-America and more are still coming to light in informal archives.

10) Long live the radical campus

The long shadow of Cecil Rhodes

It was exciting to be at the University of Cape Town in the midst of the Rhodes Must Fall campaign. This is a student-led movement with complex objectives but in essence it is a struggle to decolonise the curriculum (and more) and to bring about greater racial equality within the staff and student body. Its defining moment was the decision by the university administration to remove the statue of Cecil Rhodes that commanded a central space in front the campus. Rhodes infamously declared that he would build UCT “out of the kafir’s stomach”, in effect by docking the pay of black mine workers to starvation conditions.

Smaller actions, like the students’ relabelling of university toilets as ‘gender neutral’ were a reminder (to me) of how the arbitrariness of social category systems have a very different resonance in a South African context, where a racial fiction once defined not only your right to use a specific toilet, but your right to an assumption of humanity.

This blog is rarely updated! Want an email notification whenever there is a new post? Click on the button up top that looks like this: