What I will not do

In the interests of transparency about my methods, it is important for you to know that I will never publish any text that was generated by AI, nor any text produced with assistance from AI.

I will also never read any synthetic text, if I have become aware that it is synthetic.

I will not accept student work that has relied on generative AI, even such ‘benign’ applications as Grammarly, nor will I read or review papers and books written with any kind of generative AI interference. I will not coauthor papers with scholars who use AI to generate text for that paper, even if it is used for modifying English-language expression.

By generative AI I specifically mean systems built on Large Language Models or image repositories that are designed to produce ‘interpretable content-like substances’ (to paraphrase Michael Pollan). Applications that sometimes fall under the broad banner of AI such as neural networks and other non-generative analytical tools are fine by me. I am, for example, a cautious and intentional user of constrained machine-translation based on structured corpora but if I ever go so far as to publish a translation it will always be my own or it will be attributed to its human translator.

I don’t particularly care if someone uses AI-generated code for the sake of automating an inconsequential task. It becomes consequential if that code is then embedded in a research methodology and the individual is unable to answer a reviewer question about it.

Why I will not do it

“Using AI in education is like using a forklift at the gym. The weights do not actually need to be moved from place to place. That is not the work. The work is what happens within you.” — Sam Halpert

“No friction, no flame” — Guante

I want to be clear about my values so you know how to teach me, be taught by me, or collaborate with me.

I reject the view maintained by some lecturers that we should instruct students in how to use AI skilfully, such that they can harness its benefits and minimise its risks. My rejection stems from the fact that we are in a profession where natural human learning, insight, expression and creativity are not extracurricular options but are the foundations of the entire enterprise. The aim of writing an essay, an academic article or a thesis is to arrive at knowledge. It is never to produce a slick and frictionless consumer product. My personal view is that the process of arriving at knowledge and the material output of that process cannot be disentangled. When that process is hijacked the resulting ‘knowledge’ is degraded, even if it looks cute and shiny.

If you accept all this reasoning but still resort to using generative AI to help ‘come up with ideas’, please resist! Creativity is a muscle to be exercised regularly. Selecting a path from a set of ready-made options and then redirecting that path with your own personal spin, will only grant you the illusion of creativity and you will be become a duller person over time.

“it feels like our own aliveness is what’s at stake when we’re urged to get better at prompting LLMs to provide the most useful responses. Maybe that’s a necessary modern skill; but still, the fact is that we’re being asked to think less like ourselves and more like our tools”—Oliver Burkeman

I do not see any viable use-case scenario for synthetic text, or synthetic images, except for generating bullshit as bullshit. Eg, drafting mission and vision statements. In other words, if I can ever be convinced that there is ‘task’ that can be solved with synthetic text, it means that the task itself was bullshit to begin with. Harry Frankfurt’s explanation of ‘bullshit’ as tangential or indifferent to the truth, rather than false, is a good way of understanding the ambivalent nature of synthetic text.

Certainly a human being with the appropriate expertise can assess synthetic text and modify it so that it is aligned with existing knowledge, but that merely draws attention to the authority of human knowledge and the parasitic nature of generative A.I. As Tressie McMillan Cottom put it, “A.I.’s most revolutionary potential is helping experts apply their expertise better and faster. But for that to work, there has to be experts”.

Please believe me that I’m not trying to virtue signal or claim moral purity. If you enjoy using AI, or you’re entertained by it, or you’re excited by its promise, don’t let me be a downer. I do hope that when you enjoy it you can also reflect on what’s going on. If you think AI is ‘helping you’ I hope you are able to articulate what you believe you are releasing yourself from when you use it, and to consider whether that sacrifice is worth it.

Don’t be angry, be curious

‘Be curious!’ is advice to myself, more than to you. The hype, naivety, and fatalism around AI is very depressing to me, even before I contemplate the repulsive broligarchs who spruik it and the environmental costs of powering it.

But in more lucid moments I remind myself that I am someone who is interested in the weird and culturally relative ideas that people have about language. I have great curiosity about what linguistic intersubjectivity really means in situations where the interlocutor is absent, or imaginary. For example, what do people say they are doing when they profess to communicate with deceased ancestors, animals or gods? Similarly, I have a long fascination with linguistic utopianism, ritual speech, divination and revelation.

With this curiosity in mind I wonder what it means for an individual to assume that AI is not just sentient but greater-than-human or perhaps even godlike? What are they doing when they use anthropomorphising language such as ‘hallucinate’, ‘read’, ‘learn’, ‘understand’ or even ‘intelligence’? In what ways are enthusiastic AI-users influenced by (or captured by) internal cognitive biases, ambient linguistic ideologies, or other contextual variables such historical circumstances, politics or religious values?

One day I might revisit my hard rule about never reading synthetic text, if it is for the sake of understanding, in ethnographic terms, why sensible people might choose to engage with it. I confess that I’m not there yet! For now, I’m sitting with the struggle.

Organic text in defence of prestige

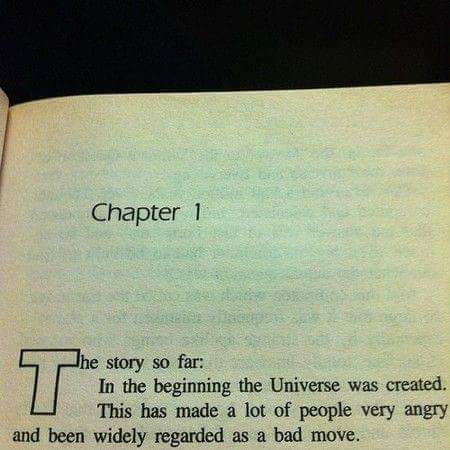

As novelist Craig Shackleton put it “LLMs are the ultimate expression of right wing anti-intellectualism. Its proponents are literally mocking the idea that anyone would ever want to learn anything, know anything, develop any actual skill, or have a thought of their own”. The utopian counterpoint to this position is perhaps even more depressing: that LLMs are here to solve ‘problems’. To take this line seriously involves inhabiting an ontology in which you convince yourself that world itself is a problem, that humanity is a problem, that individuals relating to each other is a problem, that doing anything at all—thinking, sharing, growing, adapting, working, loving, grieving—represent varieties of friction or ‘bugs’ in the system that we all desperately need to be delivered from. The worldview that underpins these assumptions is a nihilistic vision in which the aim is not transcendence but elimination. Douglas Adams foreshadowed the universe-as-problem mentality in the famous opening lines of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

Sadly, LLMs appear to be thriving in an already degraded information environment in which all kinds of naivety get a free pass. But I hope, perhaps just as naively, that the enshittification cycle will loop back around again. The disappointments of synthetic text will pile up and the advantages of unadulterated ‘organic’ text growing from sharp human minds will resurface. This is what I want my policy to be contributing to. Enough of us need to hold the line and reject the hype-and-doom narrative and defend the value of expertise until we don’t need to anymore. This essay by Iris Meredith conveys some of the optimism that I feel about this approach. It’s about focusing on prestige over status. You should read the essay to understand what she means.

What’s your policy?

I don’t expect everyone to agree with my policy on AI, but I think it’s really important to have a policy. Tell me what yours is.

Note that text above is released under CC BY-NC 4.0 which means that you can remix and adapt it to write your own policy as long as there is no commercial intent. (Trust me: you can do this adaptation without resorting to AI.)