Dr Piers Kelly is a linguistic anthropologist at The University of England, Armidale, affiliated with the Centre for Australian Studies at the University of Cologne.

OrcID: 0000-0002-6467-2338

ARC Grant number: DE220100795

Mastodon

❦ ❦ ❦

Communication is a foundational process underpinning all human activity. I am interested in one intriguing aspect of this bigger story: how the scope of ordinary language is creatively extended through strategic interventions. This is why my research is concerned with topics such as graphic codes, language engineering and crosscultural literacy, and why I find the holism of linguistic anthropology to be an especially useful tool of enquiry.

Language engineering and linguistic utopianism

Since 2006 I have worked directly with speakers of the Eskayan language in the Philippines. Members of this community maintain that their language was the creation of the ancestor Pinay, who fashioned it from parts of a human body. Pinay is also credited with the creation of a unique and highly complex script for representing his language in written form. The suprising and recent emergence of the Eskayan language and its script is the subject of my book published within the series Oxford Studies in the Anthropology of Language.

Graphic codes

Much of my current research is concerned with the ways that conventional visual sign systems originate and evolve, how they do communicative work, and how their scope is constrained or amplified by their contexts and pragmatic conditions.

Much of my current research is concerned with the ways that conventional visual sign systems originate and evolve, how they do communicative work, and how their scope is constrained or amplified by their contexts and pragmatic conditions.

Reinventions of writing

I have long been interested in those remarkable cases when writing has been independently recreated by non-literates, especially in West Africa, Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Even though these reinventions are rare they reveal important insights about our relationship with the written word and shed light on the origin and development of writing itself, arguably the world’s most transformative yet misunderstood technology.

Erhard Schüttpelz has written, in a soon-to-be published monograph:

“The emergence of writing has not been a new beginning of language but, as far as it can be reconstructed, an improvisation in which language reduction and language virtuosity merge and are often realised with the same means.”

This idea of virtuosity, constraint and manipulation perfectly captures my approach to the invention of writing.

Non-linguistic graphic codes

Writing is a very specific variety of communication employing visual marks to model linguistic structure, but it is surprisingly recent in human history and has been invented only a few times. Many other kinds of conventional graphic sign systems that do not purport to represent language have pre-dated writing and continue to coexist with it. Far from instantiating a ‘primitive’ form of ‘proto-writing’, these non-linguistic codes are finely attuned to the needs and interests of their users. They can be employed to resolve complex coordination problems over time and distance, reinforce verbal interactions, circumscribe identities, tally goods and notate categories. The visual systems at play are similarly diverse, ranging from compact linear forms to diagrammatic, multi-textual or three-dimensional techniques.

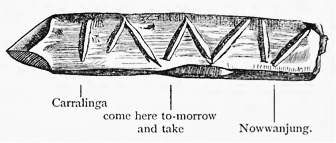

My research currently centres on Australian message sticks. This Indigenous system involves the use of marked wooden objects as aids for long-distance communication between communities speaking different languages. My study is based on fieldwork with senior messengers in Arnhem Land, substantial archival records, and over 1700 message sticks conserved in museums worldwide that are now indexed in the Australian Message Stick Database.

View my current projects here.

My theoretical orientation

Historical anthropology

I’m drawn to work that seeps into the cracks between between linguistics, anthropology and historiography. I especially enjoy ethnographic efforts to recover human experiences that are otherwise suppressed or distorted in colonial discourses. I have been inspired by the realisation that—despite its grand claims for itself—colonialism is never truly hegemonic. It breaks down in fascinating ways, and its terms are often manipulated, subverted and creatively appropriated by its presumed ‘subjects’. For decolonisation efforts to be meaningful I believe in the importance of attending to these many moments of rupture and bringing them into the light. In the same spirit I reject efforts to ‘rehabilitate’ Indigenous cultural forms by shoe-horning them into colonial categories and metrics, for example ‘agriculture’, ‘nationhood’ or ‘writing’, among other naturalised concepts. Instead, I believe in the value of recognising practices and epistemologies on their own terms, as independently powerful systems that have the capacity to be analysed, understood, re-interpreted and respected.

Decoloniality

Since I adhere to a materialist definition of decoloniality—whereby a genuinely decolonial project involves the literal return of stolen land, resources and knowledge—I cannot in good conscience argue that my scholarship is decolonial, even when it has decolonial consequences. Instead I would position my work as belonging to the postcolonial paradigm to the extent that I aim to recuperate Indigenous knowledge from distorted colonial sources in a way that is stringent, collaborative, historically informed, useful to Indigenous communities and respectful of ownership. In so doing I take inspiration from the New Philology movement associated with Edward Said, especially to the extent that it intersects with linguistic anthropology’s concern with ideology.

I maintain that Indigenous Knowledge Systems are themselves rigorous and empirical. What they are not (despite the claims of prophets and charlatans) is diffuse, vague, mystical, intuitive or New Agey. Thus, when it comes to field methods—as opposed to archival methods—I am especially interested in analytical Indigenous-devised and Indigenous-centred approaches that take an Indigenous epistemology as a foundation, even if the results may be translated with varying degrees of success into other kinds of discourses.

From this perspective I argue that classical Participant Observation is not a Western invention but merely a Western rediscovery: of the fact that knowledge derives from material and symbolic practices, and that it is relational, personal and contingent. I am sympathetic to Yarning and Standpoint Theory but do not see these as substantially distinct from good ol’ OG participant observation. (Moreover, these terms can be used as a cover for undirected and unfocused scholarship.) More concretely I am interested in Australian Indigenous techniques of recording, reporting and representing, and in the anthropology/philology of historical Aboriginal thinkers like David Unaiapon, Toolabar, Patyegarang and others. I am committed to collaboration and co-authorship with Indigenous colleagues and wherever my conclusions diverge from Indigenous co-authors I make this clear in the text without antagonism: decoloniality, after all, entails acknowledging the reality of incommensurability.

The familiar strange, and the strange familiar

I’m irresistibly drawn to all the quirky, weird and ecstatic things that people do with language or with representations of language. The cardboard-crown wearing princess who lived on the top of a mountain and interpreted the glossolalia of her elderly mother. The anti-colonial rebel leader who was said to have preserved his revealed script by having it tattooed on his body before he disguised himself as a Buddhist monk. The talking statues of Rome that write poems critical of civil authorities.

Certainly I am happy to indulge in a bit of schlock-horror Ripley’s believe-it-or-not sensationalism, but I also want to understand the backstory that positions these practices in a larger historical narrative, the contexts that make them anthropologically meaningful, and the theories that make them intelligible.

Some of the texts that have informed my research direction and general intellectual outlook are here. My evolving attempt at understanding the value of linguistic anthropology as a practice is here.

Publications

All my publications can be viewed or downloaded here. I love any kind of feedback and I’m always happy to read papers in my field. My personal policies on publishing are here, and my policies on reviewing are here.

Media

I believe in the obligation of scholars to give meaningful explanations of their work. You can find my writing on Rappler, The Conversation, Crikey, Sapiens, and other forums.

❣ ❣ ❣

What is the origin of the quotation “the familiar strange, and the strange familiar”? It’s surprisingly hard to find but he original source of ‘the familiar strange’ quotation is T. S. Eliot, of all people, writing about Andrew Marvell: “And in the verses of Marvell which have been quoted there is the making the familiar strange, and the strange familiar, which Coleridge attributed to good poetry”. It’s from Eliot, T. S. [1921] 1932. “Andrew Marvell.” In Selected essays by T. S. Eliot, 292-304. London: Faber & Faber. p. 301

Pingback: A tale of two scripts: Linear B and Cherokee – It's All Greek To Me

Pingback: The Philippine Cinderella – Notes from the Odd Side