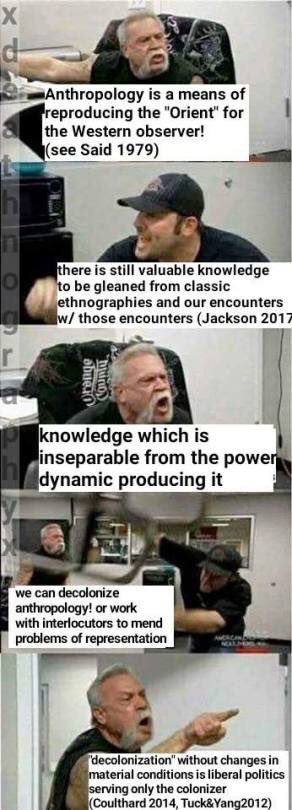

I keep thinking of this American Chopper meme and why it makes me laugh but also bugs me. The argument of the moustachioed man is one that is familiar to me but I find it to be naive. When such pure standards are set for decolonial methodologies, the baby is inevitably thrown out with the bath water. As Graeber and Wengrow put it: “To say Mi’kmaq thought is unimportant would be racist; to say it’s unknowable because the sources were racist, however, does rather let one off the hook.”

(And to be abundantly clear, Said (1979) and Tuck & Yang (2012) are not really saying what the meme suggests they are saying.)

Critics of anthropology typically fail to register the existing critiques that were generated within the discipline itself. A native title colleague once told me how tired she was sick and tired of anthropologists representing Indigenous people as remnants of a ‘Stone Age’ past, unaware of the fact that anthropologists turned against the unilinear progressivist model over a century ago even if this trope took on a life of its own in popular culture, from from National Geographic to Indiana Jones. Anthropologists themselves have a habit of self-flagellating rather than doing the harder work of articulating the liberating potential of anthropological knowledge. This is after all is an intrinsically radical methodology where the aim is to understand diverse societies by representing them on their own terms and according to their own categories, rather than through the orientalising templates of the late nineteenth century. Howard Morphy captured the anthropology-as-strawman dynamic perfectly when he wrote:

Anthropology, perhaps the most reflexive of Western disciplines, has fallen victim to other people’s reflections on it. It has listened to the assault from outside and taken the responsibility upon itself. Yet ironically, most of these critiques have initially developed within anthropology, and become anthropological orthodoxy before being taken up by outsiders, and have then been reabsorbed as if the original view were external. If anthropologists have hoped to benefit by their honest acceptance of criticism from other disciplines, they have failed to realize that the consequence of that assault was to deny the validity of anthropological practice and to allow others to appropriate the subject of the discipline.

Anthropology is threatened because it has failed to recognize the inherent radicalism of its own history. Anthropologists have become obsessed with criticisms of what they once were or of outdated theoretical perspectives

Neither was it outsiders who pressured anthropologists to decolonise. Decolonizing Anthropology: Moving Further toward an Anthropology of Liberation was published all the way back in 1991, as the outcome of a meeting held by the Association of Black Anthropologists in 1987. Were these anthropologists “serving the coloniser” with their “liberal politics” simply because they are unable to meet an impossible standard of redressing unequal material conditions? Once again, rather than dealing with complexity, the external critic is left off-the-hook.

Coloniality is not totalising. It just wants to be.

Anyone who works seriously with archival materials knows that knowledge is distorted by the power dynamic producing it, but it is never completely in its thrall. It has its own mercurial logic that very often eludes the structure that hopes to contain it. Edward Said is easily invoked by those who want to bring the news about the orientalist foundations of anthropology while his subsequent call to action is conveniently ignored.

I feel like picking up a chair and throwing it across the room just to emphasise that Said’s methodological program is all about how to do the the liberating work of reanalysis, knowing that this work will never be perfect and never be finished. Denying any possibility of reading against the grain, or finding the countersign (per Bronwyn Douglas), is to take colonial discourse at its word and to hand it all the easy power that it pretends to have already.

It’s also a neat pretext for denying Indigenous voices simply because you don’t like the packaging they arrive in, per Graeber and Wengrow’s critique. And quite apart from being a bit self-satisfied and activist-splainy, this denial amounts to accusing Black and Indigenous anthropologists of double consciousness, rather than being much better informed about the dynamics of knowledge and interpretation than you are.

To paraphrase Said himself, “read a fucking book” (Said 2004 ,’The return to philology’). OK, well not exactly but that’s the gist.

To stake my own position, I identify more as a postcolonialist (per Said) than a decolonialist. This is because I believe that the philological reinterpretation of the colonial archive has a power that is far from being exhausted. It is as much a scientific act as a political act. Similarly, I take a materialist view of decoloniality, per Tuck & Yang, which means rejecting insipid ‘decolonise consciousness’ sloganeering. Reinterpretation does not, by itself, impel real changes to material conditions, but it is certainly not antagonistic to such shifts.

Years ago, during the Rhodes Must Fall campaign, I asked a professor of philology at the University of Cape Town how it was that some non-white students like himself were able to graduate at all under the apartheid regime. He said that it was simple: racist ideology loves to project itself as totalising but it never fully succeeds. This is just the kind of gritty optimism—capable of containing contradiction and generating material gains—that should precede the troubling task of reading colonial texts.